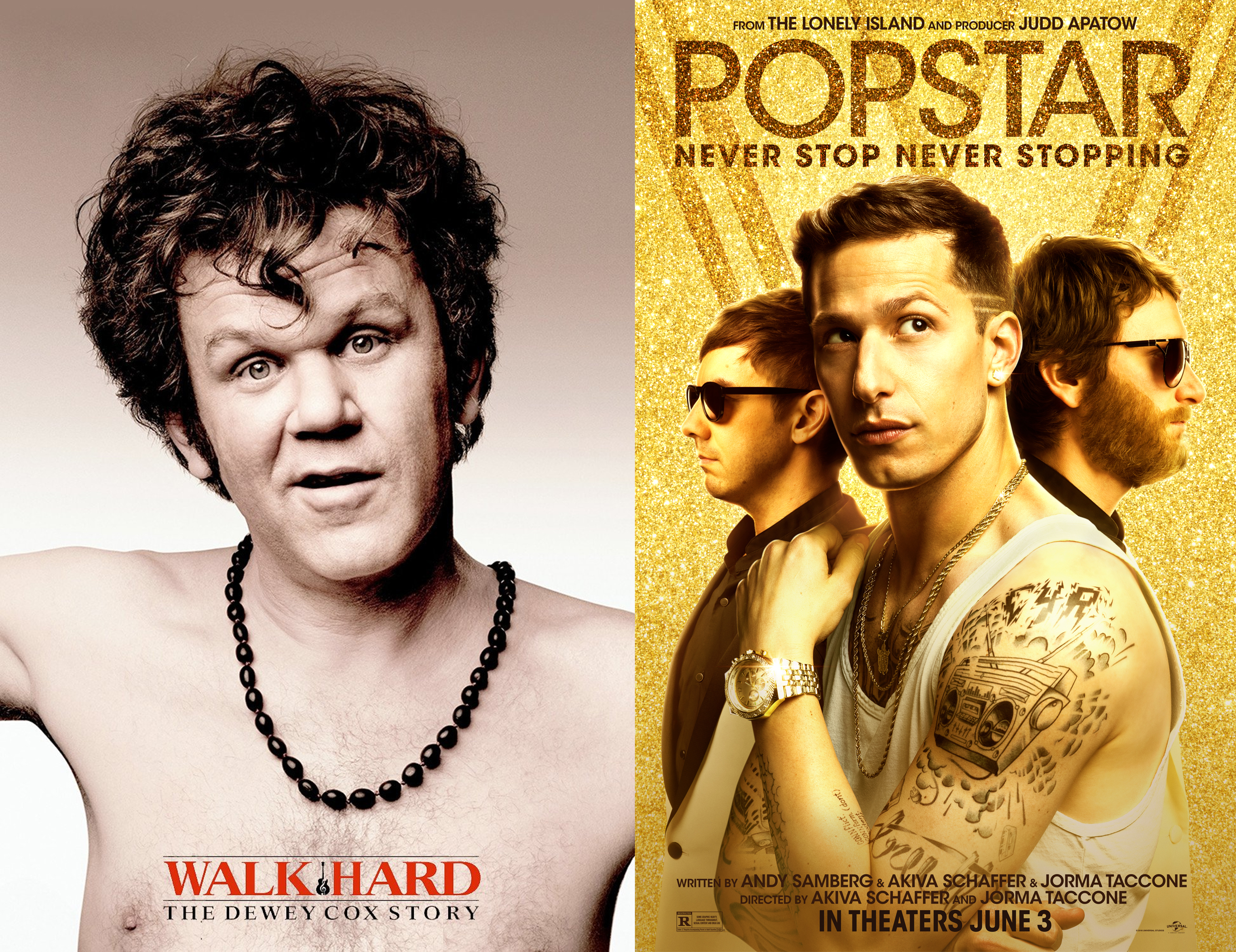

This is a fantastic double feature, and not just because they’re two criminally underrated parodies of musical pop culture. Both films are hilarious, sure, but they also offer unique yet complementary critiques of American mythmaking.

Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story (2007) was released at the height of the mid-2000s musical biopic frenzy. Ray, Dreamgirls, and Walk the Line were raking in box office dollars and Oscar nominations all over the place. The musical biopic has its own narrative language that was desperately in need of skewering- the hardscrabble upbringing, a savant-like talent, a meteoric rise followed by a descent into debauchery, and finally, a tragic death (or triumphant Vegas residency). Walk Hard hits every point so thoroughly, and with such gleeful silliness (“I’ve gone smell-blind!”) that it became effectively impossible to make another music biopic ever again. The most recent high-profile attempt, starring Tom Hiddleston as Hank Williams, bombed horribly. No one even remembers the title. Try to name it; you can’t.

It isn’t just the biopic formula that Walk Hard skewers, but the cultural legacy of all these baby boomer rock gods. The music biopic is also a bootstrapping success story- one in which raw talent automatically translates into fame and fortune. It’s taken for granted that these successes are deserved. Whether it’s Jack White’s deranged, karate-chopping Elvis, or Jack Black, Paul Rudd, Jason Schwartzman, and Justin Long delighting in delivering the worst Beatles impressions ever captured on film, these legends are sweetly punctured, underscoring the absurdity of fame, wealth, and its attendant indulgences.

The movie is also really just very funny, and John C. Reilly is one of the greatest comedic actors of our time.

* * *

It is the easiest thing in the world to make fun of Justin Bieber. He’s self-obsessed, vain, and shallow. He’s had so many PR disasters in his ten-year career that if you were just to enumerate those, you barely have to write a joke. Fortunately, Popstar: Never Stop Never Stopping (2016) sets its sights higher than this.

Within the first few minutes, the film establishes Conner4Real (our Bieber stand-in) not just as a millennial superstar, but as the fulcrum of a complicated machine; publicists, makeup artists, producers, engineers, choreographers and, of course, the requisite entourage, make up the network of adults whose livelihoods depend entirely on the mass appeal and success of this adolescent boy.

If Walk Hard is poking gentle fun at bootstrapping myths, Popstar is about the dystopia of late capitalism. The record industry of the previous generation has been turned inside out by the digital revolution. There are fewer slots available at the top, and we demand more from the people who make it there: more spectacle, more branding, more youth. Conner4Real, like Bieber, was discovered via YouTube at a young age, and is quickly molded into a marketable, appealing object. He’s alienated from his family and friends, and struggles to retain a sense of identity when the branded version of his self is staring him in the face from billboards and screens everywhere he goes.

The film is stuffed with celebrity cameos and knowing references to real child stars, but it remains refreshingly human in its portrayal. Conner’s anxiety about his success is only partly ego driven; it’s also clear he feels pressure to keep supporting the fame machine that depends on him. His insecurities ring true, and the arc of his relationship with his childhood friends/ fellow StyleBoyz is sweet and heartfelt.

The songs are consistently good, too! My least favorite thing in comedy songs is when the chorus endlessly repeats the same joke without building on it; Andy Samberg and the Lonely Island are adept at avoiding this trap. Each track takes the subtext of pop to its logical, insane conclusion, like this one that equates jingoistic military fervor with lust for a girl who’s like, really hot. It’s absurdly over-the-top and also entirely plausible.

* * *

Both films stand on their own as sharp, silly comedies, but they also work together as a shrewd examination of the mechanisms of fame.